The practise of Yoga has amassed great popularity in the past few decades. There is growing anticipation about how wondrously healthy of a practice this is. The true meaning of Yoga has somewhere been reduced to a florilegium of thousands of postural regimes. The history of Yoga & its concept (along with various physical postures or asanas) has got recent attention globally. However, trailing through the evolution of the modern yogic concept, it can be inferred that the practice has a more spiritual element attached to it than it has been in execution.

History of Yoga –

The word ‘Yoga’ is derived from the Sanskrit word ‘Yog’ which means ‘union’. Yoga is one of the 6 ‘Darshans’ or Hindu philosophy. It is an organized system of physio-mental relaxation and fitness techniques woven subtly with mood-stabilizing characteristics. A yoga practitioner, called a ‘yogi’, is mentally absorbed in such a practice. Organically, it implied the union of a mortal human’s spirit with an immortal divine’s spirit. However, the modern amateurs attempt to achieve a physical benefit out of this, also claiming to have worked out with a somewhat elusive trace of mindfulness. It is believed to synthesize one’s mind with the body. Thence, yoga as a voguish concept differs markedly from the original tradition.

People are becoming more conscious of their own well-being and are taking up this refreshing hobby. Indeed, yoga has a lot to offer. It is proven to improve one’s flexibility, helps in weight reduction, tones muscle, helps the individual have a night of better sleep, better concentration, better relaxation, and subdued distress. This results in a balanced mood and an energetic self. To grasp the true essence, we would have to go back in time that spawned various aspects and the history of yoga.

The birth of yoga is estimated to have taken place in the pre-Vedic times during Indus-Saraswati Civilization, about 5,000 years ago. It grew strong in its philosophical depth during Vedic times when the Mahajanapad kingdoms shaped India’s social history. Yoga was a means of gaining celestial powers, achieved with equally intensive practices. Yoga’s evolution is divided into 4 periods: Pre-Classical, Classical, Post-Classical and Modern. However, the original raison d’être of practice varied over time. In ancient oral traditions, yogic practices were meant to evoke self-realization through action, wisdom and knowledge, sacrificing materialistic greed and ego.

This was a raw form of yoga where postures hadn’t solidified yet and deep meditation largely influenced it. Thereafter, the written scriptures came into existence in which enlightenment (Nirvana) became a priority. It became more extensive. The embedded spirituality turned towards physical excellence in the Post-Classical Period where techniques were mastered to gain physical strength. Much of the modern concept of well-being is the outcome of such exigent physical magnification. The marked metamorphosis is elucidated below.

Proto-Historic Period (3000 – 600 B.C.)

Legends speak of Lord Shiva, the Adi yogi (or the first yogi) and Lord Vishnu drowned in deep meditation. Lord Shiva gifted the science of yoga and extreme penance to the Saptrishi (Seven Sages) who refined it for the use of by the common earth-dwellers. This period marks the advent of yoga. In ancient times, the teachings were dependent on oral tradition.

Shreds of evidence of yoga have been found on seals from the Indus-Saraswati Civilization period in which the heavenly figures sustain a posture (Mulabandhaasan) which imply a greater emphasis on the subject back then. Though the seals alone can’t affirm the existence of science and with a huge lack of historical evidence from ancient times, we come to conclude that a crude form of yoga should have been practised before.

Pre-Classical Period (600 B.C. – 200 B.C.)

Brahmins and sages had access to the Vedic texts (4) which contain hymns and rituals. They propagated their knowledge through teaching and concretion of the socio-cultural system began. Yoga had its first mention in ‘Rig Ved’ supplemented heavily with spirituality. Much emphasis was laid on how an intense personal sacrifice can garner energy and tranquillity. Atharvaveda introduces ‘Vratya’ ascetics who came up with bodily postures that may have shaped yoga asanas we practice today.

Saptrishi are believed to have modified it and compiled their practices into Upanishads (108). Katha Upanishad says ‘yoga’ for the first time. Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (earliest Upanishad) indicates ‘Pranayam’. Chandogya Upanishad mentions ‘Pratyahaar’. The Jaiminiya Upanishad Brahmana writes about controlled breathing and Mantra chanting. Maitrayaniya Upanishad writes about 6-fold yogic method consisting of Pranayam, Concentration, Meditation, Reasoning, Spiritual Absorption and Pratyahara.

The Indian Epics, Ramayana and Mahabharat, incorporate many instances of hard penance. The text of Bhagwat Geeta emphasizes 3 major types of yoga, Karmayoga (Actions), Gyanyoga (Wisdom) and Bhakti Yoga (Devotion). It came around 500 B.C. and is considered the best yogic scripture. The essence of yoga was to achieve through actions. Constant practice, mental concentration and detachment were called for.

‘Shraman’ (originated from the word ‘Shram’ meaning ‘hard work’) movements arose during 600 B.C. in the area of Ganges-Yamuna. They developed techniques of meditation that help achieve Moksha (liberation from the cycle of birth and re-birth). They ran in parallel to the Vedic mainstream. Buddhist culture of meditation finds its roots in the constant meditative imagery of Gautam Buddha. It was through profound meditation that he achieved enlightenment (knowing the ultimate realities of the world).

Early Buddhist texts indicate that ‘Dhyan’ (meditation) and ‘Tapas’ (inner heat/self-discipline) predominated the yogic concept. These two paved the way for self-realization. About this time, asceticism (self-mortification) had matured in the practical sense. The Pali Canon contains that Buddha’s description of pressing the tongue against the hard palate to curb hunger. Satipatthan sutta is the foundation of the contemporary Vipassana meditation. Anapanasati Sutta details the breathing practices.

The Jain concept of yoga houses austerities and fierce penance. This practice helps the individual achieve liberation (Moksh). Tapas is of great importance and such control of desires was believed to assist the purification of the body. The Jain yogis would fast, bear all sorts of hardships and live with an iota of essentials. Bahya Tapas cultures renunciation practices while Abhyantar Tapas means an overt expression of pure thoughts.

Another sect, Ajivika, adhered to extreme asceticism in isolated caves, forests, mountains. Ajivika meant that the follower of the sect has no free will and there should be full command over life choices combined with a pre-determined path of life. For them, yoga was largely based on Tapas and Niyati (destiny). “Everything in human life and universe, according to Ajivika, was pre-determined, operating out of cosmic principles, and true choice did not exist.”

Classical Period (200 B.C. – 500 A.D.)

This period is symbolized by an organized yogic practice prescribed in Patanjali’s ‘Yogasutra’ that was developed during 200 B.C, ‘Yog-Yagyavalkya’ by Yagyavalkya, ‘Yogcharbhumi’ and ‘Vishuddhimarg’.

Yogasutra is the first formal amalgamation of yogic sciences. Its seed is found in the worship of Shiva (Purush, static-like the soul) and Shakti (Prakriti, dynamic like the flora and fauna). It defines the 8-fold path of yoga or ‘Ashtaang’. They are:

yama niyama āsana prāṇāyāma pratyāhāra dhāraṇā dhyāna samādhayaḥ aṣṭau aṅgāni

Moral restrains, recommended behaviors, body posture, breath enrichment, sensual energy withdrawal, linking of the attention to higher concentration forces or persons, effortless linkage of the attention to higher concentration forces or persons, continuous effortless linkage of the attention to higher concentration forces or persons are the eight parts of the yoga system.

- Following Ahinsa (non-violence), Satya (truth), Asteya (to not steal), Brahmacharya (celibacy) and Aparigrah (non-possessiveness).

- Observe Sauch (purity), Santosh (contentment), Tapas (austerity/meditation), Swaadhyaya (self-reflection/study) and Ishwarpranidhaan (supreme self),

- Aasan (meaning ‘seat’), to be in a seated posture when meditating,

- Pranayam (controlled breathing),

- Pratyahaar (withdrawal of external disturbances that received through senses)

- Dhyan (Meditation)

- Dhaaran (Fixating/Absorbing)

- Samaadhi (liberation/union with the universal self)

According to Yogasutra, Chitt/Man (psyche) is always disturbed and is in the state of ‘vritti’ (activities of the intellect and mind) because of the wavering nature of the senses and the mind. When Chitt-vritti is brough under control, the Sakshi Purush (absolute self) attains his true state.

This silencing of Chitt-vritti is yoga. As the mind and the Praan(breath that creates a fine biochemical substance which works in the whole organism and is the main agent of activity in the nervous system and in the brain.) are inseparable from the body, to bring the body and the breath under control, the practice of ‘Aasan’and ‘Pranayam’ is prescribed.

tīvrasaṁvegānām āsannaḥ

For those who practice forcefully in a very intense way, the skill of yoga will be achieved very soon.

samādhi bhāvanārthaḥ kleśa tanūkaraṇārthaś ca

t is for the purpose of producing continuous effortless linkage of the attention to a higher concentration force and for causing the reduction of the mental and emotional afflictions.

prakāśa kriyā sthiti śīlaṁ bhūtendriyātmakaṁ bhogāpavargārthaṁ dṛśyam

What is perceived is of the nature of the mundane elements and the sense organs and is formed in clear perception, action or stability. Its purpose is to give experience or to allow liberation.

These excerpts from the text reflect the spiritual aspect of yoga:

Īśvara praṇidhānāt vā

Or by the method of profound religious meditation upon the Supreme Lord.

kleśa karma vipāka āśayaiḥ aparāmṛṣṭaḥpuruṣaviśeṣaḥĪśvaraḥ

The Supreme Lord is that special person who is not affected by troubles, actions, developments or by subconscious motivations.

atra niratiśayaṁ sarvajñabījam

There, in Him, is found the unsurpassed origin of all knowledge.

asya vācakaḥ praṇavaḥ

Of Him, the sacred syllable āuṁ (Oṁ) is the designation.

tajjapaḥ tadarthabhāvanam

That sound is repeated, murmured constantly for realizing its meaning.

dhāraṇāsu ca yogyatā manasaḥ

and from that, is attained the state of the mind for linking the attention to a higher concentration force or person.

The text, hence, added a fourth ‘Rajayog’ to the 3 major types of yoga emphasized by Bhagwat Geeta. ‘Raja-yoga’ implies the ultimate goal of yoga, that is, Samaadhi.

Yogasutra apart from inculcating valuable information about spiritual gains of yogic system, also enlightens about basic practical and universal truths.

anubhūta viṣaya asaṁpramoṣaḥ smṛtiḥ

Memory is the retained impression of the experienced objects.

duḥkha daurmanasya aṅgamejayatva śvāsapraśvāsāḥ vikṣepa sahabhuvaḥ

Distress, depression, nervousness and labored breathing are the symptoms of a distracted state of mind.

maitrī karuṇā muditā upekṣānāṁsukha duḥkha puṇya apuṇya viṣayāṇāṁ bhāvanātaḥ cittaprasādanam

The abstract meditation resulting from the serenity of the mento-emotional energy comes about by friendliness, compassion, cheerfulness and non-responsiveness to happiness, distress, virtue and vice

pracchardana vidhāraṇābhyāṁ vā prāṇasya

or by regulating the exhalation and inhalation of the vital energy.

‘Yogasutra’ has influenced the modern application of Yoga. This period witnessed shaping of Hindu culture and revamping of the Hindu divinities through the scriptures available to the language masters.

संयोगो योग इत्युक्तो जीवात्मपरमात्मनोः॥

Yoga is the union of the individual self (jivātma) with the supreme self (paramātma).

The aforementioned text has been taken from ‘Yog-Yagyavalkya’. It discusses eight yoga Asanas – Swastik, Gomukh, Padma, Vira, Simha, Bhadra, Mukt and Mayur, numerous breathing exercises for body cleansing, and meditation.

Vaisheshika Sutra of the Vaisheshika Darshan of Hindu philosophy describes Yoga as “a state where the mind resides only in the soul and therefore not in the senses”. This is indicative of Pratyahara or withdrawal of the senses and the ancient Sutra asserts that this leads to an absence of sukh (happiness) and dukh (suffering), then describes additional yogic meditation steps in the journey towards the state of spiritual liberation.

Post-Classical Period (500 A.D. – 1700 A.D.)

This period sustains the birth of ‘Tantra Yoga’. ‘Tantra’ means a technique or method. The ancient practitioner refuted the Vedic norms and modified the mainstream spirituality-based yoga for physical strengthening and preservation of energy. The static body is the centre of energy and these are spiked up with techniques. The development of energy is focused on the purification and cultivation of prana and the activation of ‘Kundalini’.

‘Kundal’ literally means ‘coiled’ or ‘circular’, ‘Kundalini’ indicates a feminine form of the word because it is a form of Shakti (feminine form of power which is dynamic). It consists of 7 Chakras that activate from the base of the spine. To activate this energy and attain ‘spiritual liberation’, Tantra yoga presents various types of Aasans and meditative Mantras. As the ‘Absolute-self’ progresses, all the 7 Chakras activate one by one up till the head. This results in enlightenment, realization of the self, earnest consciousness, calmness, compassion and detachment from negative emotions. The practice calls for mental and physical purification to begin with.

Tantra Yoga is inclined towards attaining enlightenment through physical well-being. This type is practised today to cultivate power, clarity and confidence. Popular postures included in this type are – Tadaasan, Utakataasan, Bitilaasan to Adho-Mukh Swanaasan, Virbhadraasan, Prasaarit-Padottaasan, Ardh-Navaasan, Tadaka Mudra, Praan Mudra Shavaasan etc.

It caused ‘Hatth Yoga’ which is popular in western culture. The word ‘Hatth’ means ‘force/stubbornness’. The poses are sustained for a longer duration of time and achieved by slowly ‘pushing’ yourself thus enhances flexibility.

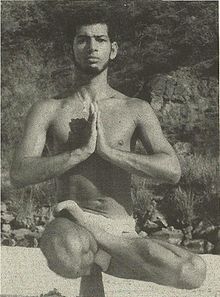

Hatha Yoga Pradipika came into existence in 1350 A.D. Different types of Aasan, Mudra, Pranayama were compiled by Yogi Swatmaram. The first chapter starts with Aasans. It names 15 postures.

The first 11 are Svastikasana (auspicious posture), Gomukhasana (cow face posture, legs), Virasana (hero posture), Kurmasana (tortoise posture), Kukkutasana (cock posture), Uttana Karmasana (intense tortoise posture), Dhanurasana (bow posture), Matsyasana (fish posture), Paschimottanasana (intense West side stretch posture), Mayurasana (peacock posture), and Shavasana (corpse posture).

It then describes four seated postures: Siddhasana (perfect posture), Padmasana (lotus posture), Simhasana (lion posture), and Bhadrasana (fortunate posture). The last four were taken from Lord Shiva’s total of 84 lakh postures.

The teachings of great Acharyas – Adi Shankracharya, Ramanujacharya, Madhavacharya-were prominent during this period. During the medieval period, Bhakti Movement pressed upon love and devotion to a personal deity. This played a significant role in the rejuvenation of Bhakti yoga all over India.

Modern Period (1700 A.D. – Present)

The global postulation of yoga includes subtle cultural assimilation. The pre-modern yoga experts spread the knowledge of yoga to the west. Much of the work was done by the Hindu preacher Swami Vivekananda who popularized Karmayoga, Gyanyoga, Bhaktiyoga and Rajayog in the west.

With colonialism in the Indian sub-continent, was encouraged and travelled internally and further. The adaptability of this practice was distinctive. Raman Maharshi, Ramakrishna Paramhansa, Paramhansa Yogananda, Vivekananda etc. contributed to the development of Raja Yoga.

This is the time when Vedanta (another Darshan), Bhakti yoga (path of devotion), Hatha-yoga flourished. The Shadanga-yoga of Gorakshashatakam, Chaturanga-yoga of Hatha-yoga Pradipika, Saptanga-yoga of Gheranda Samhita, were the main pioneers of Hatha-yoga. Swami Krishnamacharya opened the first Hatha yoga school in Mysore in 1924. Swami Shivananda wrote over 200 books on yoga and established numerous ashrams and yoga centres around the world.

Yoga is now practised all over the world for physical benefits. International Yoga Day is celebrated with great fervour on 21st June every year. In India, the various sects follow different schools of yoga to attain a varied sense of consciousness. It is exercised as a physical well-being tool and also as a distinctive relaxation technique.

Yoga has turned into a vital contrivance that assists in healthy living. For people living in the new age, overburdened with daily stressors and demanding situations, devoting some part of the day comes as a natural beneficiary.

Mental stability can be achieved through various meditative and breathing techniques. There are various psychologists, spiritual gurus, lifestyle coach who swear by the idea of simple yet effective yogic practices. With every passing year, the global health initiatives have proved to be productive to improve the health quotient of many.

Through the ages, the history of yoga transformed from an intense spiritual practice to a system of physical rejuvenation technique. It played an important role in bringing solace to people and it continues to do so.

FAQs

Q.1 When did yoga evolve?

circa 3000 B.C.

Yoga began as an ancient practice that originated in India circa 3000 B.C. Stone-carved figures of yoga postures can be found in the Indus Valley depicting the original poses and practices

Q.2 How has yoga evolved over the years?

Yoga began in Northern India 5000 years ago. The word “yoga” was used in sacred texts that consisted of their songs and other rituals.

Q.3 What is the development of yoga?

In the age of the Upanishads, the idea of yoga became a technique of entering the body of another human being. By the time of the Mahayana Buddhism, the techniques of meditation once again got combined with visionary procedures.